As nationalism sweeps Europe, a subtle cinematic triumph about an unlikely subject animates the hopes of transnational democracy

David Bernet hates carpets. Particularly sturdy, institutional carpets; “the ugly kind that last forever”. But in his latest film, Democracy, the 49-year-old Swiss film-maker has spent five years treading the carpets of Brussels. He’s been following a process with an uncertain ending, in an aesthetic he finds displeasing, to direct a wholly original film about the machinations of European law-making.

Democracy, opening this week in Germany, is a determinedly European film. It is also a subtle, human, optimistic, sensual portrayal of something that for most people couldn’t be further from those descriptors: data-protection reform.

Bernet’s stylish, monochrome sequences cut through the convoluted layers of Brussels bureaucracy, as well as what he describes as the stomach-churning ugliness of its carpets and halls, to find a story of collegiality and hope. At its heart are two idealistic Germans, Green MEP Jan Philipp Albrecht, and his right-hand advisor, tech geek Ralf Bendrath. In a captivating 100 minutes, we see Albrecht struggle against all odds to manoeuvre the unwieldy tanker that is the European Parliament through two years of negotiations, an armada of lobbyists, endless shadow meetings and 4,000 amendments towards a consensus data reform proposal in early 2014.

Kind, diligent and well spoken, Albrecht is an effective tousled frontman for modern politics. But so too, perhaps surprisingly, is another of the film’s heroes: long-serving EU commissioner, now parliamentarian, Viviane Reding. In Bernet’s sympathetic portrayal, Reding is multilingual, magnetic, relentlessly committed to the public good, and effuses warmth, support and sincerity.

Both Albrecht and Reding grow over the course of the film, which was shot intensively over 30 months. They are rounded out by a cast of intriguing characters who trail tantalising hints of their lives beyond Brussels, as well as their motivations for joining the debate. Joe McNamee, executive director of European Digital Rights, excels as a dystopian Cassandra. “People will realise how important this process is, in two, three or five years. But then, the process will have passed,” he says, eyes blazing. He’s complemented by the passionate, persuasive activist Katarzyna Szymielewicz and, on the business side of the equation, experienced Linklaters partner Tanguy Van Overstraeten and enterprising business lawyer Paolo Balboni.

Conspicuous in their absence are the major lobbyists. Facebook lobbyist Erica Mann appears briefly, but despite persistent efforts, Bernet was unsuccessful in bringing Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon and the other data giants into the discussion; though they were constantly present and omnipresent, “everywhere, all the time”. As Bernet explains, “these companies have a strong policy not to be mentioned in the context of data protection or privacy – they are all denying to be part of it”. The only lobbyist who appears in the film is John Boswell, of SAS, the data prophet who also opens the trailer. “He comes from a family company, not listed in the stock exchange. They have nothing to fear from the public opinion. That’s interesting,” says Bernet.

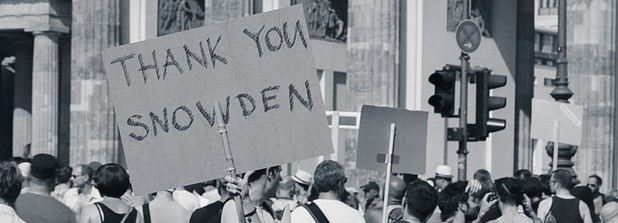

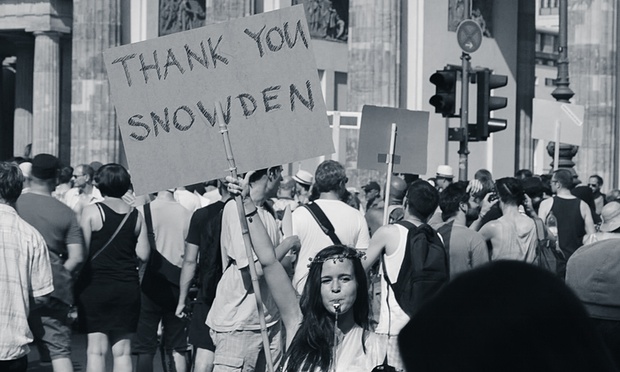

The real change of pace in the film hits at 80 minutes, with the Snowden revelations. Few venues were more primed for the whistleblower than the meeting rooms of Brussels. We feel the resonance and heartbeats as the negotiators receive a cameo from former Guardian editor, Alan Rusbridger: “Anybody who uses digital equipment is put under some form of surveillance. It seems to me that that cannot happen without consent, it cannot happen without the consent of populations. So, my message to the lawmakers is: please protect us.”

The conviviality of the parliamentarians is palpable, “sitting together continuously, week per week per week”. By the film’s end, it is a joy to see hugs and true satisfaction across the faces of MEPs that started the film at a distance, from the slick-haired, braces-clad Dimitrios Droutsas to the concerned-for-business Sarah Ludford, and from the magnanimous Seán Kelly to the unlikely ally Axel Voss.

While Bernet was lucky to find an ending in the notoriously drawn-out and ongoing reform process, it is a bittersweet one. A December finish is promised for current trilogue negotiations between the European Commission, Parliament and Council, which are expected to water down the consensus we see in the film. Meanwhile, unresolved tensions simmer at the heart of data protection law, which asks too much where it shouldn’t, and too little where it should. And, in parallel, state surveillance rides on, virtually unchecked. “It seems we don’t need time to eliminate the rights, but we need a lot of time to augment the rights,” Reding says, in a pointed challenge to governments. “Where is the equilibrium?”

Bernet is sensitive to this too. “At the moment what we have is a kind of Faustrecht, or law of the fist, in cyberspace. The strongest takes it all,” says Bernet. “A friend of mine told me, we are only in the Middle Ages of digitalisation. The Renaissance has yet to come. But I do think that Brussels is key to defining the rules of the future.”

Bernet first had the idea to make a film about how a law comes to life a decade ago, while working on a film about interpreters, The Whisperers. “But it was clear that to do it, you needed a really tough debate. It has to be a law that affects everybody; that promises some heat, ideologically, economically, politically. The privacy debate is clearly a debate at the heart of democracy. Not only in the sense that individuals must be free to make their own decisions, to exercise free will, to not have their autonomy limited by algorithm. But also, in terms of protecting minorities and individuals. This is why we need fundamental rights. We must know where surveillance starts and ends.”

“As a Swiss, at first I was sceptical of Brussels,” says Bernet. Now he’s an admirer. He sees the complex layers of interests and processes as a strength. “Complexity is what interests me as a filmmaker. Making complex areas of life and institutions accessible. In Brussels, complexity is a peace concept. It is really avant-garde – and national media can’t, and don’t, cover the dynamism. We live in a generation of governments all over Europe that don’t really participate in the creation of the union. This is a selfish way of doing things.”

“From the beginning, the plan with this film was to use an aesthetic that is completely different from what we are used to when we see reports about Brussels. It always has the same facades; people arrive in limousines, you see the flags, the yellow stars. Apart from the opening scene, I have forbidden my team to film flags. This is to make clear to the audience that this is something different – this is not a report, this is not news, this is really offering you an experience from a different quality.”

In offering this experience, Bernet’s film is a triumph. It rewards contemplative viewing and is a visual delight, with a lovely play between the inner and outside worlds of the EU institutions, in a style reminiscent of Terrence Malick. Hopefully, too, it draws a wider audience to the critical importance of data protection and the conflicts that surround it.

As for Bernet, he’s enthusiastic about next projects. One centres on the famous Israeli musician, Daniel Barenboim. “It’s mostly about politics – war and music,” he says. And he’s started digging into the global network behind the World Economic Forum, which he’ll be filming over the next two years. “That’s more a film about post-democracy, a network of the global economic elite.” Realising that many more conference rooms and halls lie ahead, he laughs. “The WEF will be really a carpet film, too.”

Fonte: http://www.theguardian.com